A fascinating insight

Ali Shakir interviewed by Niran Bassoon-Timan in Arabic allows us a fascinating insight on the reason he chose to translate Violette’s memoirs above all the others available on the same subject.

A fascinating insight

Ali Shakir interviewed by Niran Bassoon-Timan in Arabic allows us a fascinating insight on the reason he chose to translate Violette’s memoirs above all the others available on the same subject.

In case the link I previously posted (last item, Cut!!) doesn’t work, please try this:-

Lessons from Baghdad’s Jewish Community’s History – رصيف 22 (raseef22.net)

I’m sure you’ll remember our friend Ali Shakir, a Baghdad-born writer who has translated Memories of Eden into Arabic (now enjoying significant success across the Arab world, I’m happy to say). Ali lives in New Zealand, and was invited to join a BBC radio discussion concerning the 1941 Farhud on the 80th anniversary of the pogrom earlier this year. As a Muslim, his input would be particularly welcome to the debate.

Like us, everyone we know was greatly looking forward to the conversation –– and then the intended broadcast date came and went without it. Oh well, these things happen as I know only too well as an old journalist: what’s topical and important one moment gets degraded on the newslist as more vital information attracts the editor’s eye. One can only hope that the recorded segment might survive and be put on air later, as its significance can hardly be said to have diminished. All that is without considering the extremely hard work and engagement the BBC staff and freelance helpers (I’m thinking of our niece, Violette’s grandaughter Sarah, in particular) put in to organising the session.

Eventually, it aired. After months of delay, Sunday on 19 September went out with an extremely truncated, lightweight, version of what we had been led to expect. Our disappointment was nothing compared with the sense of let-down felt by the programme participants –– none less so than by Ali himself. Quite how much effort and hard work he had put in to the project in answering emailed questions from the producer on the other side of the world we can now tell, as he has published his answers on his own blog which you can see here.

Lessons from Baghdad’s Jewish Community’s History raseef22.net

It’s been a while but finally I’m happy to announce that a Kindle version of “Memories” is now available on Amazon. This is the link for the UK site. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Memo…/dp/B09C6DW4M5/ref=sr_1_1

It is also available elsewhere on Amazon (France, Germany etc) although for rights reasons not in North America. In the United States and Canada, Northwestern University Press has a printed version as well as its own Kindle edition.

What makes this new version especially interesting and different is that the old photographs have been colourised, bringing the story to life as never before. I find it quite astonishing. You might be interested in having this even though you already have the print version. I have also added some new information to the section “Behind the Farhud” that has come to light since the book was first published in 2006. And there are loads of fabulous new photos and illustrations. Another attraction (I hope!) is that we have priced it modestly at £7.

I would be very grateful if you would share. You might also like to watch the YouTube video of slides we have compiled with Iraqi music which replaces and improves the one that was posted over the last 15 years and counted over 150,000 views.

https://youtu.be/sstMk245rqo

Amazon’s UK site has been without copies of Memories of Eden for some time. Sold out, I hope! We’ve sent a new supply and everything is back to normal now.

There’s a bit of confusion because the US edition is selling there as a Kindle version, a pound dearer, and the American paperback also which is £5 dearer. I’m trying to sort that out and thinking of replacing the lot with a Kindle version of our own, which should be considerably cheaper.

The following comes from a Dubai-based Armenian reader of Iraqi origin:

“I always cherish the book you had sent me (Memories of Eden) by your neighbour Mrs. Violette Shamash, it is a wonderful book and it did bring back some many memories, and explained many things that I did not know about- but had taken them for granted. Baghdad is a rich city in its history, traditions and people, but sadly today much of it is getting erased.”

I’ve mentioned before that Memories of Eden is now available in Arabic, thanks to the initiative of Ali Shakir, a Baghdad-born writer who lives in New Zealand. His charming essay describing his experience has just appeared in a respected New Zealand magazine, Arab.Lit, which I am pleased to reproduce here.

By Ali Shakir

Each time I watch or listen to immigrants and refugees describing their arrival in their hosting environments as a happy ending, I can’t help feeling a little suspicious. I understand they want to express their gratitude. And there is definitely a sense of euphoria, and of “making it” at the beginning. But based on my first-hand experience, turning the page on one’s past is not even an option. There’s never an ending.

A silver lining to the dilemma, though, is that the journey often pushes us to attend to our long-silenced questions. Shortly after reaching New Zealand’s impossibly distant shores in 2008, I felt an overwhelming urge to understand what had happened in Iraq, and the Middle East at large. I needed to read books written from different perspectives about our history and politics. New Zealand allowed me to do just that.

I still remember my excitement when I realized I could finally read any book I wanted: old and new, in any language, and from any part of the world. No banned authors, no torn-out pages or lines and images thickly obscured by a censor’s permanent black marker, all of which had tried—often uselessly—to curb my insatiable hunger for books while growing up in Ba’ath-ruled Baghdad.

I immediately indulged in the all-you-can-read buffet, and was particularly interested in books that explored the Middle East’s many cultures and faiths. I was also curious to learn more about the plight of the Iraqi Jews, who’d made up nearly a quarter of Baghdad’s population in the early 20th century and were considered the oldest Jewish diaspora community in the world. In 2006, only a dozen was left, all of whom feared for their lives and aspired to migrate.

Having familiarized myself with the topic; shortly after sending my third book to press in 2018, I decided my next project was going to be an Arabic translation of one of those documents. Violette Shamash’s memoir Memories of Eden, however, was not my first choice. I wasn’t looking for a script on traditional recipes or the evolution of clothing styles in Iraq after the end of World War I. I wasn’t willing either, to recount the jokes of coffee-shop patrons, housewives’ gossip, and the pranks young schoolgirls had pulled on their teachers. I was searching for a shocking testimony of a survivor; a manuscript that encapsulated the pressure endured by the Jewish community before and after their nearly-forced departure from the land where they’d lived for millennia, a story about the agony of separation and fleeing ethnic cleansing.

That was the plan, but Violette’s intimate recollections of the banalities of her early life were almost impossible to resist. No sooner had I started reading the first chapters/letters than I was taken by her charming Mesopotamian storytelling. My defenses crumbled, and despite an old pledge never to cry over Iraq, when I finished translating her emotional farewell to Baghdad, tears were rolling down my face.

True to the memoir’s subtitle, A Journey Through Jewish Baghdad, she took me on a guided tour that delved into different stations. She welcomed me into her family house and its vast garden overlooking the Tigris, where we indulged in the scents of blooming gardenias, jasmine, carnations and jouri roses wafting through the air, with mouthwatering aromas of freshly baked bread. We ate fruit that she snatched from the trees before heading to the Jewish quarter and its famed Hennouni market, where the family used to live before her father’s decision to build a qasr (villa) on the capital’s then-outskirts.

Violette made me follow her through serpentine alleys to the Alliance School, where we heard young girls mischievously whispering and giggling in their classrooms, and their teachers reprimanding them. And when the night fell, we took our seats around a band of Jewish musicians and singers to listen to their enchanting, if a little lamenting maqam tunes.

Her generation had seen Baghdad undergo a reshuffle of colonial powers—from the Ottoman Empire to the British, and its people start to enjoy the amenities of contemporary Western life, such as paved roads, electricity, telephone service, drinking-water supplies and sewerage, as well as cars and public transport, cinemas and radio service. And the fancy novelties of social clubs and department stores.

What struck me while scrutinizing those details—and would motivate me further to proceed with my project—was that a lot of what Violette had mentioned in her letters was no longer there. Names of once-famous singers, markets and neighborhoods, foods and proverbs; they had all disappeared from our collective memory, and the references made to them in her book may well be their last.

Halfway through the process, it dawned on me I’d taken a ridiculously long detour to a nearby destination. Despite the fact we never met in person, and an almost 60-year age gap; a bond of wonderful rapport grew up between Violette and me. She’d become a family member; a grandmother who had an almost inexhaustible reservoir of fascinating tales. Only the stories she narrated about our homeland were in English, and it was my duty now to retell them in Arabic. I had to retrieve her Baghdadi voice without making her sound too local, given that several of the book’s anecdotes are as relevant today as ever. They eerily echo the ordeals of millions of contemporary Iraqi and Arab refugees and immigrants, including me.

The Jewish community’s serenity in modernized Baghdad was short-lived, sadly. They quickly became scapegoats for all the injustices caused by British colonialism, and were increasingly targeted by members of the rising Arabist and Islamist movements over the large-scale immigration of European Jews to Palestine. The tensions came to an appalling peak in what is known as the Farhud of 1941—a two-day pogrom against Baghdad Jewry inspired by the Nazis.

“When we got to the Farhud, Violette wrote to me that she could not go on. It was too painful and she wanted to skip it,” Mira, Violette’s daughter said in an email. She and journalist husband Tony Rocca are the memoir’s editors. It took some convincing before Violette finally agreed to disclose the details of what happened during those 48 hours. Soon after, the family packed their bags and left Iraq. None of them has returned since.

Now that my translation is released, I must admit my work on it has been quite therapeutic. I have gone through some rough times in the past three years—including the latest episode of Covid-19—but then I’d read a letter on how Violette had continued to enjoy music, food and jokes until the very end, and my despair became irrelevant. She had every reason to hate and seek revenge, but chose to let go and never give up on hope.

I hope her story will similarly influence other Iraqis and Arabs struggling with difficult situations, inside and outside their countries of origin. My Jewish grandmother, I’m certain, wouldn’t have wanted a better outcome.

*

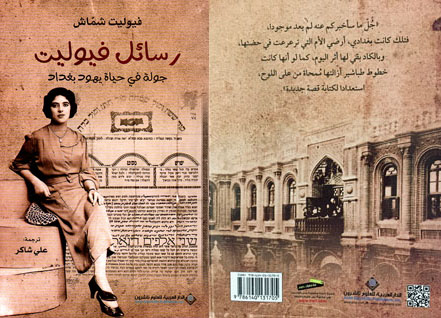

رسائل فيوليت: جولة في حياة يهود بغداد (Letters by Violette: A Journey Through the Life of Baghdad Jewry) was recently published in Beirut by ASP INC.The introduction to the Arabic edition explains the change in title.

*

Ali Shakir is an Iraqi-born, New Zealand-based architect and author. His articles, essays and reviews—in Arabic and English—appeared in many newspapers and literary journals in the Arab world, the UK, the United States and New Zealand. He is a member of the New Zealand Society of Authors, former blogger for The Guardian Weekly, Huffington Post (in Arabic) and a regular contributor to Arcade (Stanford University) and Raseef22.

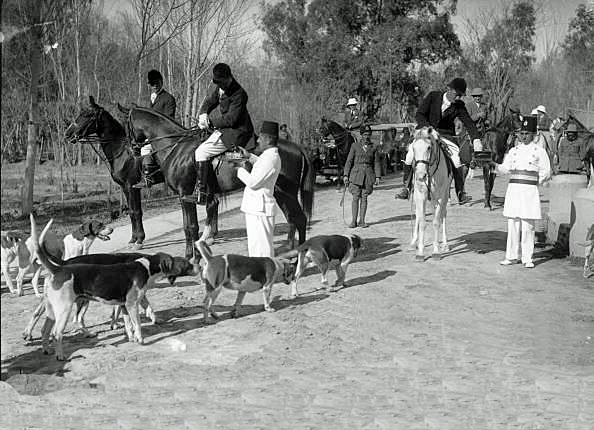

Welcome to the Royal Exodus Hunt, pictured in 1934 in the countryside near the River Tigris where horse and hound could be seen around the RAF airfield south-east of what much later came to be known as Baghdad’s Green Zone. It was the pukka thing, complete with elaborate kennels, thoroughbred horses, Indian servants and a Master of Hounds.

We came across it while researching Memories of Eden. It’s rarely remembered today, but Britain created the state of Iraq and ruled it under a mandate until 1932. It treated the country as “India Lite”, with a strong presence of troops from the sub-continent.

Fox-hunting had always been popular in Mesopotamia, so the idea of riding to hounds the English way seemed a natural progression when polo, games of mah-jongg, and shooting trips for duck, snipe, partridge and quail failed to satisfy the colonial lust for recreation and craving for blood sport.

The Exodus Hunt as it was called centred on a pack of hounds belonging to a unit of the Indian Army known as the 110th Transport Company, and gained its name from the Hindustani for the number 110 — “ex sao das”. Members rode both Arab horses and English thoroughbreds. The hounds were an exotic cross-breed collection of saluki Gazelles and fierce Kurdish sheepdogs, donated by local notables and tribal chiefs in exchange for free membership.

In its first season the pack killed a wolf, 17 jackals, three foxes, a cow and an old woman, who actually died of fright. The Master of Hounds went by the nickname “Brassneck”, a monicker earned on a very alcoholic night when he dived into what he thought was a swimming pool only to find it void of water . It was a pit of dry concrete.

Luckily, Brassneck suffered no ill effects, which is more than can be said for Iraq itself.

The hunt kept going until 1955 when it was disbanded.

TONY ROCCA

After many years of success with the book, first in English (2008, 2010), then Hebrew (2014), we’re delighted to report that Memories is now available in Arabic. This is thanks to yeoman work by author Ali Shakir, an Iraqi from Baghdad who lives in New Zealand. The book has just been published in Beirut by Arab Scientific Publishers under the title “Violette Letters: A Tour in the Life of the Jews of Baghdad” and is available online:

https://tinryurl.com/y2vodq13 or https://tinyurl.com/y27xvtzy (Neelwafuran.com)

It’s lovely to think that Violette’s words can now be read in her original language and we wish Ali every success with the project, with our thanks and gratitude for all his hard work.

With this development I have found it appropriate to update the video I made a few years ago (which has been watched more than 150,000 times according to YouTube). Ali has kindly suggested I use some Iraqi music as background this time and I enlisted his help in selecting a few pieces. I hope you like the result. Please share!

Dear Mira (a reader writes),

I just started reading this beautiful memoire and got to Page 14 which talks about Beit el Barazali. My paternal grandfather bought Beit El Barazali from your grandparents, and he and my grandmother along with my 2 uncles and their wives and both my parents lived there.

Throughout the years we always heard talk of Beit El Barazali. My maternal aunts and uncles and my mother grew up next door to Beit El Barazali, and my then youngest little uncle as a child says he remembers a Moshe living in the house at the time. Throughout the years growing up my mother and father always talked about living in Beit El Barazali as a newly wed couple along with my dad’s brothers and their wives and parents. It was a very large house indeed with a Bustan belonging and next to it.

My grandfather sold the house years later and it became a court house and sectioned into offices. What a small world. We immigrated years ago, and live in NC.

Nedda Ibrahim